FIU med school takes on Miami’s many underserved neighborhoods

By Joseph Sturgeon

Cooper City High School

Hundreds of thousands of working-class Americans cannot afford a hospital visit and about 530,000 families go bankrupt each year because of unexpected medical emergencies, according to CNBC.

Florida International University’s NeighborhoodHELP initiative is aimed at combating that issue in Miami-Dade communities. The program, based at the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, specializes in researching the social determinants that cause certain illnesses in underserved communities, and works to provide free treatment and services to the uninsured in these areas.

The South Florida Business Journal reports that Miami-Dade has one of the highest uninsured rates in South Florida.

Approximately 20% of the county’s residents had no form of health insurance in 2017. The county’s current uninsured rate is about half of what it was in 2013 but with a population of nearly 2.8 million people, the number of people without health coverage is still about 550,000.

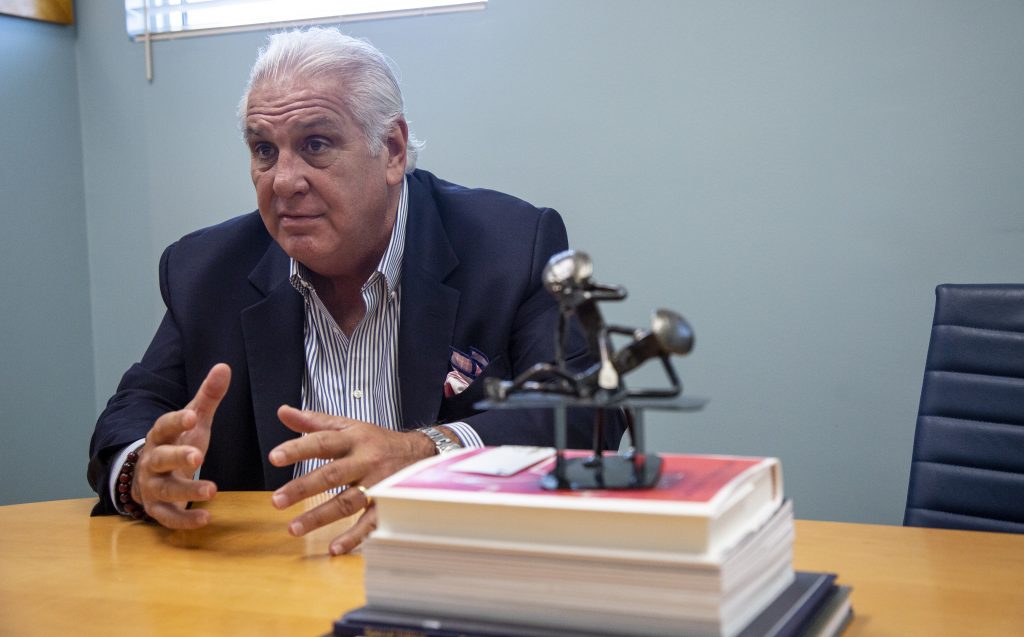

“If you’re working two or three jobs just to make ends meet and you don’t have health insurance, it means you don’t have benefits at work,” said Dr. Pedro José Greer, chair of FIU’s Department of Humanities.

“For you to go see a doctor, it means you’d have to take a full day off of work, which means your family [with] very little is going to make 20% less that week. This financial burden that we put on people [makes them] wait until they’re really sick, so their family doesn’t suffer.”

FIU’s medical, social work, law and education students work under the NeighborhoodHELP program, pooling their skills to help meet the needs of the community.

Launched in 2009, the program provided support to 436 households from July 2017 to June 2018, amounting to 1,277 patients cared for. The patients are treated by trained HWCOM students who travel from the college to their patients’ homes to tend to their needs.

Disparity in access to adequate healthcare between low-income and middle-class families isn’t unfamiliar to many communities across the country. In 2017, researchers with The Milbank Quarterly, a peer-reviewed journal, found that nationally, those with an annual income of $25,000 or less reported receiving average or poor medical care, 30% more than those who make $100,000 or more.

In addition, a report compiled by the Miami Urban Future Initiative at FIU found that Miami has one of the highest economic inequality gaps in the nation, second only to New York City and followed by New Orleans.

“If you’re in Overtown versus Brickell Key, there’s a 15-year difference in your survival. Ninety percent of these diseases are caused by social determinants of health and [other] non-biological causes,” Greer said.

“The most important factor for survival in America is not your genetic code; it’s actually your zip code.”

NeighborhoodHELP pinpoints a community’s needs through the use of social determinants – the social and economic aspects of a person’s life that can affect their health. In addition to medical help, the program provides counseling, social support and legal services.

“I remember going into a household, and there was [this] young man, [he was] an immigrant and a student of Miami-Dade. His mother was dealing with mental health issues,” said project manager Sophia Lacroix.

“He said he’d applied for Medicaid, and had been denied, thinking that he was applying for the correct resource. We advised him of what to do, which was to go to the Social Security office. As a result, he was able to get what he needed for his mom.”

Miami-Dade County has 19 cities, six towns and nine villages. This amounts to 34 municipalities, each with its own distinct characteristics.

“Our medical schools and the health profession school can’t pretend to serve everyone,” said Frederick Anderson, medical director of HWCOM.

“That’s why we in the program have partnered with a lot of community organizations in several communities. They include Hialeah, North Miami Beach, Little Haiti, any community with longstanding health disparities.”

Greer said that access to healthcare should not be a privilege, but rather a right.

“There’s a moral obligation that we have as individuals in this position if we take it,” Greer said.

“We’re supposed to take care of people without prejudice.”