Low-income kids can beat the odds in the game of life

By Yasmine Mezawi

Miami Lakes Educational Center

Shaika Surprize is one of six siblings who grew up without a father and spent years in the foster care system. She attends the University of Central Florida after overcoming many adversities.

“Coming into college I found myself at a disadvantage,” she said. “I didn’t apply for certain scholarships or opportunities due to the fact that I didn’t know what I didn’t know.”

No one coached her on important life lessons. Starting from not being able to attend regular school field trips, to not finding a place to call “home,” she deals with the difficulties of an unstable economic background.

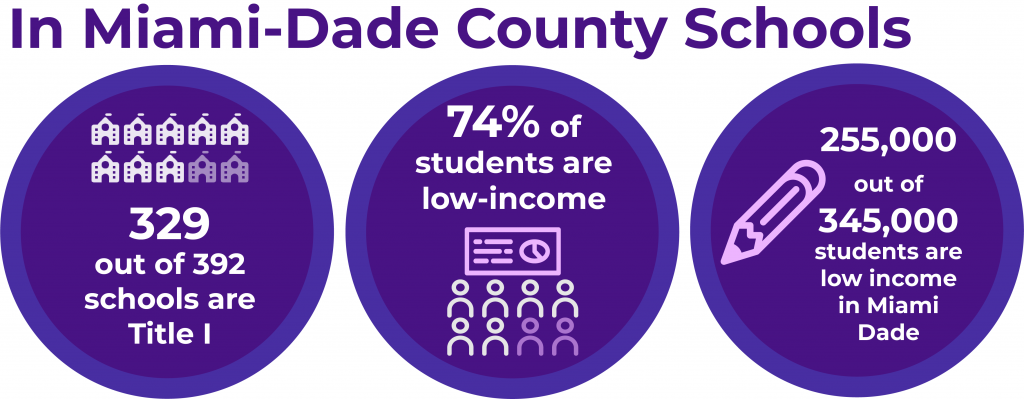

According to cityyear.org, nearly 75% of the students in the Miami-Dade school district – the fifth largest nationwide – come from a low-income household.

“I noticed between me and my peers the different levels of stability and support,” Surprize said.

Students in these homes struggle through levels of poverty and academic obstacles that create a division among students due to her disadvanage.

Surprize realized the lines of division at a young age. While her friends prepared for the next class trip, she never dared to ask her parents.

Their disadvantage became even more pronounced as Surprise got older. Without a safety net to rely upon, she entered the foster care system with four of her siblings in 2012, she said.

Her brother, Jefferson, took custody of their twin brother and sister, then 14, when he was 20.

Jefferson took them in because he “felt like if they were around family, it would be best.” They still live with him.

Taking care of his siblings during the day and attending classes at night, Jefferson earned a bachelor’s degree in Information Technology from Miami-Dade College when he was 24 years old.

Unlike her youngest siblings, Surprize lacked a strong support system and she began to see how years of neglect affected her well being. Her background correlates with her mental health issues, she said.

After being in the foster care system, Surprize was diagnosed with depressive disorder in March 2018 and attends therapy on a weekly basis.

She was forced to learn how to live on a tight budget, keeping her from participating in extracurricular activities such as traveling.

She can be found on campus while her classmates go home for the holidays. She struggles to find a sense of belonging, she said.

Low-income students face a common enemy. They must often navigate through life alone and fight the stigma of poverty that they’ll never make it out.

Rebecca Shearer, a child psychologist, studies the behavior of at-risk students and has worked with Miami-Dade county to implement programs to help them.

“The child is the center of the system and then there are concentric circles that go around the child,” Shearer said. “The first system that touches the child is the family, and the parents, the neighborhood, as well as the school setting.”

The relationships between students and their peers also are important contacts, Shearer said.

Yet, low-income students try to find the will to continue moving forward.

Sabrina Cerquera, 21, a Miami Lakes Educational Center graduate, attends Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Ore., and is struggling to provide for herself away from home.

Raised by her Colombian mother and grandmother, she is a first-generation high school graduate among her three siblings. When applying to colleges, Cerquera knew she might have to leave home, but took the chance anyway.

“Emotionally it’s really hard because I don’t get to see my family that often,” Cerquera said. “It plays a big role on my mental health because I feel really alone at times and I don’t think it’s something we talk about often enough as Latinos.”

Cerquera realizes she has risen above the low expectations set for her and other low-income students.

“I own my story and that this is where I come from and look at how far I’ve come,” Cerquera said. “And I want other people to see that and understand.”