Unique program teaches mental health in 56 Miami-Dade high schools

By Nyah Hardmon

Cypress Bay High School

Growing up, high school senior Sabrina Herrera was constantly told not to discuss mental health issues, especially not in public.

“In my family, my parents never talked about that sort of thing,” Herrera said. “If I would have told them I’m depressed they would have been like, ‘No, you’re not.’ Just complete denial.”

Sabrina Herrera, the president of Health Information Project at the Maritime Science and Technology Academy, says peer-to-peer teaching is essential for teen mental health. (Photo by: Joseph Fernandez)

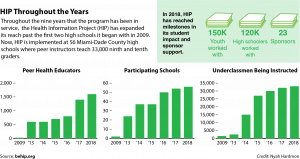

Now, as the incoming president of Marine Academy of Science and Technology High School’s (MAST) Health Information Program (HIP), Herrera teaches mental health issues to hundreds of students. The program uses peer health educators to guide freshmen and sophomores on taboo health subjects, with a special focus on mental well-being.

Because of budget cuts, staff shortages and changing graduation requirements, health education is no longer required at high schools in Miami-Dade County. HIP fills this gap by replacing health education with a high school club equipped with older teen role models, paving the way for better decision-making and open discussions about complex psychological topics.

“All parents want to help their children, but they don’t understand how to communicate,” said Herrera, 17. “We understand what it’s like to be in [the student’s] position because we were just there going through the same thing. There’s no way parents remember exactly what it was like at this age.”

HIP is in 56 Miami-Dade County high schools and has worked with more than 150,000 students. Club advisers give student leaders the liberty to run discussions and educate peers about topics from nutrition to depression with minimal adult interference.

“We’re not giving them elaborate definitions that they could find in a psychology textbook,” Herrera said. “We’re explaining it in a way we know they can understand because we understand it ourselves.”

Peers such as rising MAST senior Gabrielle Yamar put up posters with positive messages and provide students a website of health case resources.

“I think what makes [HIP] so effective is that we are constantly told to not talk about depression or bulimia, and HIP throws that out the window by providing kids with so much new information on subjects that they know so little about,” Yamar said.

Anxiety and stress are two topics that HIP instructors focused on this year because of their prevalence. Addressing issues at an early stage, mentors provide ways to combat mental struggles and stop them from worsening.

“In ninth grade, you’re entering what’s like a new world for the first time,” Yamar said. “Advanced classes and extracurriculars make you overstress and overcompensate, so we teach them how to cope with this. If you have a healthy mind and build mental strength, you can avoid a lot of poor decisions.”

Herrera is familiar with the process—on both ends.

“I was always the shoulder to cry on but would never cry on someone else’s. Other health classes would tell me to talk to my parents, but sometimes parents don’t want to admit there’s a problem. HIP helped me get through my depression by giving me someone to talk to.”

Rising MAST senior and incoming HIP Vice President Diego Garcia believes delving into mental health challenges the perception that mental conditions are less important than physical ones at an early age.

“Mental health is probably the most important module that we teach,” Garcia said. “When we talk about mental health, we are very keen on hitting every point. If you miss a point, you can mess up a kid’s life. For example, if you don’t talk about how depression can come in different forms, that it’s not just some quiet kid in a corner, then they could never get the help they need.”

During the summer, Garcia and Herrera work with other board members to prepare new peers, all of whom must complete an eight-hour workshop to learn the curriculum and classroom management.

Kristen Cope, one of the program’s first peers, worked alongside founder and CEO Risa Berrin, who started the organization after identifying a lack of health education in her community. Unlike other curricula, HIP integrated the one topic that was rarely addressed in academic settings: mental health.

When Cope joined as a Miami Palmetto Senior High sophomore, HIP was in only one other high school, Gulliver.

“We started anonymous Q and A’s throughout the school that instructors could answer during sessions for those who were more shy,” Cope said. “It allowed kids to recognize that they were allowed to talk about this stuff and let them know how to get help if they needed it.”

At MAST, HIP launched in 2016, after the suicide of freshman Zach Gustinger. The program was brought in the next year to cope with the death and educate students on handling psychological problems.

“I think that his death was a main reason HIP was brought to our school because the administration saw how heartbroken the kids were, and there was no one to help them,” Herrera said. “The effects of bringing in HIP were almost immediate. It helped them understand what happened and how to prevent it.”

Cope said she’d like to see HIP spread to other schools across the state and nation. In fact, she helped brainstorm HIP in A Box, a concept that makes the health curriculum so detailed it could be put in a box and shipped anywhere.

Child psychologist Sarah Ravin believes programs like HIP should spread to more schools across South Florida, especially in classrooms with young students.

“Mental health should be taught at an earlier age than adolescence, preschool even,” Ravin said. “Kids who get help early for mental health issues are much more likely to recover versus people who wait years and years before getting help.

Pediatric psychologist Amanda Strunin agreed.

“Teens want to feel heard, and bottling emotions in can lead to more serious health consequences,” Strunin said. “Research shows that peer group discussions and programs led by teens and focused on relevant issues like body positivity and self-esteem have a positive effect on well being.”

As much as HIP has provided a positive health outlet for students across Miami-Dade County, the program still faces challenges. Age differences and immaturity can become a hindrance to the process.

“It’s frustrating because I just want to shake them and tell them that this is for you. We’re doing this all for you,” Herrera said. “But I know that won’t help anything. That’s what a teacher would do. So I just smile, continue the lesson and hope they see the point eventually.”