LGBTQ+ students feel excluded in sex education classes

By Kaylee Hilyer

McArthur High School

Ariel Sabillon wished he had cancer rather than HIV.

“When I was diagnosed with HIV, I honestly thought it was the end of my life,” he said.

Sabillon, a 22-year-old who identifies as queer and non-binary, did not receive the sex education he needed while in middle and high school. Because of his sexual identity, he felt pressured to have a lot of casual sex, which led to him contracting HIV as a junior in high school.

“Most of my sexual education from those years came from Yahoo Answers and Google,” said Sabillon, a Florida State University student from South Florida. “If it’s not the internet, it’s community dialogue.”

The act of having sex is complex and discussing it is often taboo. Due to a lack of proper education, many people who identify as LGBTQ+ are left on their own to learn the basics and how to keep themselves and others safe.

In fact, the Guttmacher Institute, an organization dedicated to educating Americans on sexual health, reports that only 12 states discuss LGBTQ+ topics in sex education classes, with only nine of them allowed to discuss them in a positive light.

Sabillon also knew little about STD testing. He didn’t realize that he had the disease until another partner accused Sabillon of infecting him.

Although Sabillon’s HIV is now being treated, he is passionate about educating other youth so they do not end up in his position.

In an effort to determine where LGBTQ+ sex education is being taught, the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network [GLSEN], conducted a National School Climate Survey. The report indicated poor national and state leadership when it comes to developing sex education standards.

GLSEN found that even though “77.6% [of students] had received some form of sex education in school, the sex education they received did not typically include LGBTQ topics.” The survey also found that only “6.7% [of students] reported having ever received LGBTQ-inclusive sex education at school.”

As GLSEN discovered, most schools still do not include LGBTQ+ topics during sex education, despite the fact that the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in 2015. That’s because most schools have “No Promo Homo” and abstinence-only standards.

“No Promo Homo” (short for No Promotion of Homosexuality) laws prevent schools from discussing LGBTQ+ topics in a positive way in the classroom. Six states still enforce these laws but Florida is not one of them. Even so, Florida is one of 37 states that require abstinence-only sex education, which focuses only on discouraging students from having sex.

Sabillon’s experience with contracting HIV is one of the worst-case scenarios. But even students who have had an easier experience find the lack of LGBTQ+ sex education frustrating.

Christopher Beytia Frentzel, who identifies as gay, said learning lessons on pregnancy in his classes seemed irrelevant.

“Obviously, me being gay, what the f–k do they have to do with me. I just remember them showing us a pregnancy in a classroom and trying to scare us with it,” he said. “I will never get anyone pregnant, so that didn’t really scare me.”

Even with the abstinence-only model, some schools still advocate for the use of contraceptives, but the education students receive is inconsistent. This leads students to feel left out and puzzled.

“It was a very confusing time because I was just starting to have sex,” Sabillon said. “I had no way I could discuss certain things that I had to learn, and I feel like I’m just now learning those things.”

In addition to the physical consequences, a lack of education can affect students’ mental health.

“Non-heterosexual students really face dire and more severe consequences around mental health,” said Becca Mui, the education manager for GLSEN.

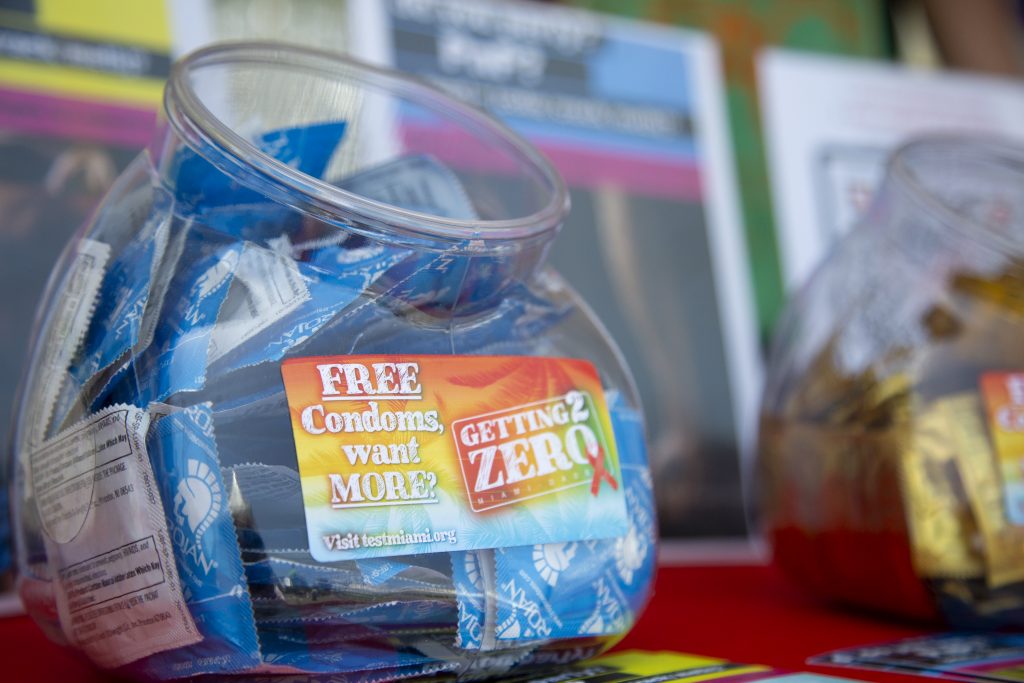

Although there is a lack of proper sex education in schools, many community-based organizations have stepped up to offer students LGBTQ-oriented education.

The YES Institute is the “only place that takes education and translates it to everyone,” said Mariana Ochoa, volunteer and former intern for the organization located in Coral Gables. “They do that through communication courses and educating the public on gender and orientation.”

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all solution,” Sabillon said. “Instead of controlling someone’s sexuality, try to work with the grain, not against it.”